Making “& metaphors”

Metaphors like machines, brick-and-mortar medicine markets, talking to ghosts, and figurative and literal dope boomerang back and forth through my work. They are a constellation of symbols spiraling like the lines on a barber’s pole through lyrics, prose, and whatever other means I can make them apparent.

I’ve thought a lot about how the United States uses Black people like an addict uses drugs. I’ve mostly described it this way when describing my own relationships to addiction and living in this country, but this version of the metaphor isn’t quite fair to people living with addiction, though.

It’s probably more accurate to say the United States uses Black people like drugs and is committed to convincing itself and the rest of the world that the country is, somehow, both a pharmacy and a trap house. It will sell you what you need out the side or back door if you want it dangerously, and if you need it prescribed, then it can sanction it and sell it to you over the counter. It’s machinic in the way it uses Blackness as a primary ingredient in the licit and illicit products it brands.

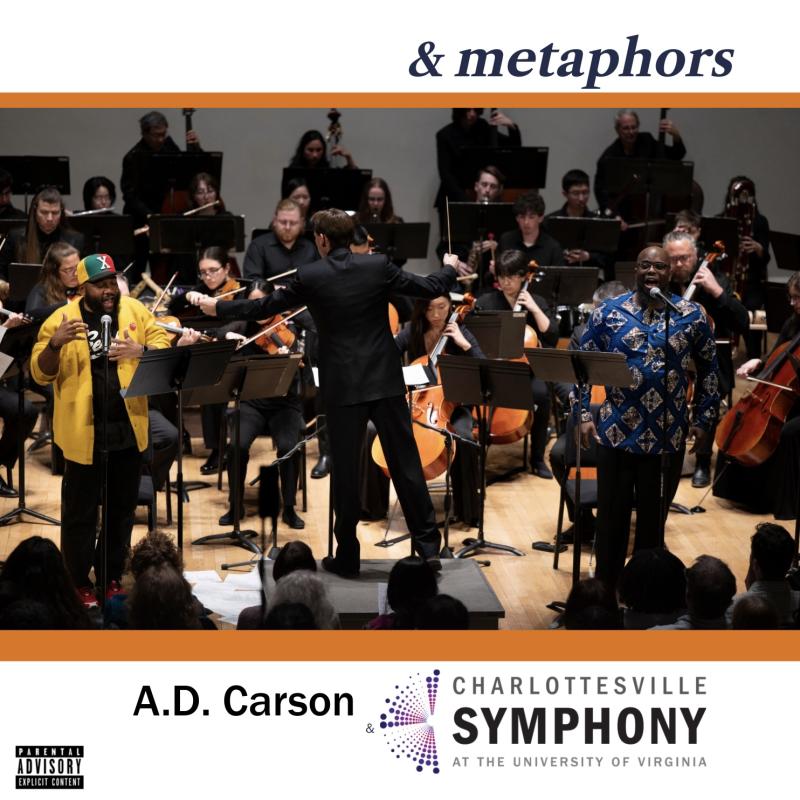

I was commissioned to write an original work for the Charlottesville Symphony at the University of Virginia’s 50th anniversary season. The piece features countertenor Patrick Dailey and shared the Masterworks program with Wolfgang Amadè Mozart’s Requiem and Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings. Saturday, March 22, 2025, at Old Cabell Hall on the Grounds of the University of Virginia, we performed the world premiere of & metaphors.

When the music director and conductor, Benjamin Rous, was preparing the program notes for & metaphors, it hadn’t occurred to me that we might need an advisory for explicit content. I wondered what the bar was for “explicit” in this context, understanding that there’s likely no shortage of violent, profane, or otherwise explicit music in this tradition. Perhaps the warning was because I would be speaking the words rather than singing. I knew the reason was probably simpler. This was likely one of those over-the-counter moments at the metaphoric pharmacy that came with a receipt and a wink that let a customer know it’s the same thing they sell through the side door. I knew the advisory wasn’t coming from Ben. Since we knew there’s a lot invested in the symphony here, we wanted to create the best conditions for an impactful artistic experience.

We wanted & metaphors to sound like a machine breaking, like something that was operating but also on the brink of exploding. There are moments that soar idealistically and suggest progress or even success, but then, just beyond the triumphant crescendo, as it seems everything might end up okay, it all falls apart in disordered failure and begins again through the break.

The lyric I wrote for “framing pain” from i used to love to dream is, “I’d rather stay and laugh than leave and sob. / I’d rather break the whole machine than try to limit me and be a cog.”

When it was released in 2020, I was writing about the distances, geographic and temporal, from my home in Decatur, Illinois to becoming a professor submitting that album, which would become the world’s first peer-reviewed rap album published by an academic publisher.

Regarding & metaphors, Ben said, “In the work, A.D. Carson not only employs metaphors, but explores the very idea of metaphor as a lens through which to view the nature of communication between opposing viewpoints. In referring to “ampersand,” he zooms in on this ancient Latin-derived symbol, which, as he has written, ‘continues to hold meaning; to connect sentences & phrases; to link pasts, presents & futures together; to suggest possibility.’ ”

Ben and I were hired during the summer of 2017. After our first faculty meeting, I was so sure I was going to be fired that I called my former dissertation advisor to tell him before he heard it from anyone else. I’m not being hyperbolic.

Though I didn’t use these words, some people might have felt that I had suggested to the room full of white folks that they were instinctively racist.

About twelve days before classes started, there was a race rally in town. Some proud white activists who wanted the world to know they were proud of being white had been campaigning all summer in the name of that cause. The season was to culminate in what they called the “Unite the Right” rally in one of the crown jewels of America’s racist relics, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Charlottesville is home to Thomas Jefferson’s primary residence and plantation, Monticello, and it was also the site of one of the most famous race war participation trophies—the bronze Robert E. Lee statue. It stood in a park downtown named for the Confederate general who lost the Civil War. Jefferson’s University is where I was hired as a Professor of Hip Hop, and I arrived in town the same weekend as one of the tiki torch march dry runs earlier in the summer.

That was in May, the same week I graduated with my Ph.D. The faculty meeting was in August.

After the first torchlit rally in May there was a counterprotest. I assume it was one of those “not in our town” type of deals. I don’t make it a habit to compare hells or devils, but white people hellbent on the weight of their whiteness are, indeed, a special breed of human. And if I’m being honest here, many of the people who present themselves as progressive are often worse. In my experience, because they don’t intend to be offensive, violent, and dangerous, they’re often certain that their actions aren’t as offensive, violent, and dangerous as their prouder white counterparts. On top of that, someone like me might find himself in a room full of formally educated, high-achieving experts in their fields who believe harm and hurt are contingent on intent more than impact. Again, I didn’t say those words.

As a student, I had well-meaning professors (and supervisors, bosses, etc.) who turned their attention to the vulnerable people after a crisis. I don’t think this is a bad thing, necessarily, but it can have the opposite effect if they used their position of trust to put us on the spot to make everyone else who’s feeling whatever they may be feeling at that difficult time feel a little bit better that they all “made space.”

In the case of the race war genre of events, and those adjacent, such as racialized uprisings, white race pride marches, and “Unite the Right” rallies, I verbalized my hope that my new colleagues didn’t use the occasion to force their racially minoritized students to bear such emotional and psychological weight.

When these kinds of things happened in my past, the folks “making space” did so with few, if any worries that they might be doing more harm than help. So, I said that it might be retraumatizing for students to be asked to re-enact, narrate, describe, or otherwise perform the horrific events of the summer now that we were back in the supposed safety of Thomas Jefferson’s classrooms.

Aghast, someone questioned in rebuttal, “Well, what should we do, then?”

To which I replied, “I don’t know.” Something else, though. Anything else.

I suggested that maybe a better course of action is that white folks talk to white folks about the real past, present, and ongoing harm done in the name of whiteness—maybe ask them questions or brainstorm about why and what they might do to confront it.

After encouraging them to use their whiteness to navigate the situation, Ben — who was a stranger to me then — asked directly, “How do we do that?”

I responded that I have never been white, and since I’ve never had much whiteness to work with, personally, I would probably be the least ideal person in the room to offer expertise on the subject. I did encourage him, though, that there was plenty of whiteness in the room, and I had faith they’d figure something out if they really wanted to.

I don’t think he assumed that I was challenging him to commission a rapper to perform with the orchestra for their 50th anniversary season, but he did eventually ask if I’d be interested in collaborating if and when time permitted.

I find it difficult to articulate how much I despise the particular genre of orchestra/rap performance that’s presented like the orchestra is doing hip hop a favor by allowing it onstage with all the other instruments. I asked if he had any ideas that weren’t in that genre and told him that I would be open to it if he could figure out why he wanted to collaborate.

Besides, I’m not so keen on performing in places like this. It feels extractive, like the emotional equivalent of what I assume it would feel like for a housefly to recreationally scuba dive in buttermilk. I’d rather not.

In my view, as a performer, if I’m being asked to do something any artist can do, then you should probably ask any of the other artists who you think can do it. If there’s something you want to work on with me, then you will be able to tell me why.

Five years and a few conversations later, Ben dropped by my lab to tell me he thought he figured out how we might collaborate. He had been studying and planning. He had ideas about what he wanted to do with the orchestra, and how my work might fit with what he had been thinking about.

I left our first planning meeting excited that what he wanted to compose together was specific to my work and ideas that he thought would make for a collaboration that wasn’t just orchestral renditions of instrumentals to my songs with me performing the lyrics onstage with everyone dressed in penguin suits.

Even though it took five years to get to it, the collaboration feels urgent and timely. That metaphoric machine that so much of my work describes grinds away daily, ever on the brink of exploding or imploding. That “Revolution” that Gil Scott-Heron famously said won’t “be televised” in 1971 has been both prescient and persistent for the past five decades. My interpolation of his potent poetry has been ongoing since 2012. I came back to it after a decade for what appeared to me to be obvious resonances. It wasn’t just the constant drumbeat of violent politics begetting importunate protest.

It seems, now, like the people rallying around whiteness in 2017 weren’t alone in their desire to make sure the rest of us feel the weight of it. They lost their Robert E. Lee participation trophy and bounced back to win the White House again, along with legislative authority to give out whatever participation prizes they feel are warranted and retroactively rewrite their losses as wins, while pretending the game hasn’t been rigged in their favor from its start.

If ever the world needed a song, a soundtrack, a sonic disruption or reckoning, it’s right now. & metaphors is music for this moment. And I hope that if it is entertaining to people who listen and watch, it isn’t only entertainment. It’s as medicinal as it is recreational, I’d argue.

I hope audiences hear it as an alternative to leaving sobbing, defying limits that would have us help the machine trying to destroy so many of us do so more efficiently. And I hope they hear that machine breaking. And I hope they hear the possibilities we’re between collectively and individually. And I hope it encourages them to try to decipher the metaphors that ask us to, somehow, see slaughter as salvation and wickedness as righteousness as the demand and supply of strange fruit insatiably increases and the human harvests are rendered unworthy of mourning by the monsters manning the machines across the world. And I hope they find the overlap of Mozart’s unfinished Requiem and Gil Scott-Heron’s untelevised Revolution without the need of a translator or crossfader. And, per se, and, &, &, &…